Celebrating Stoddart: Staff Reflections

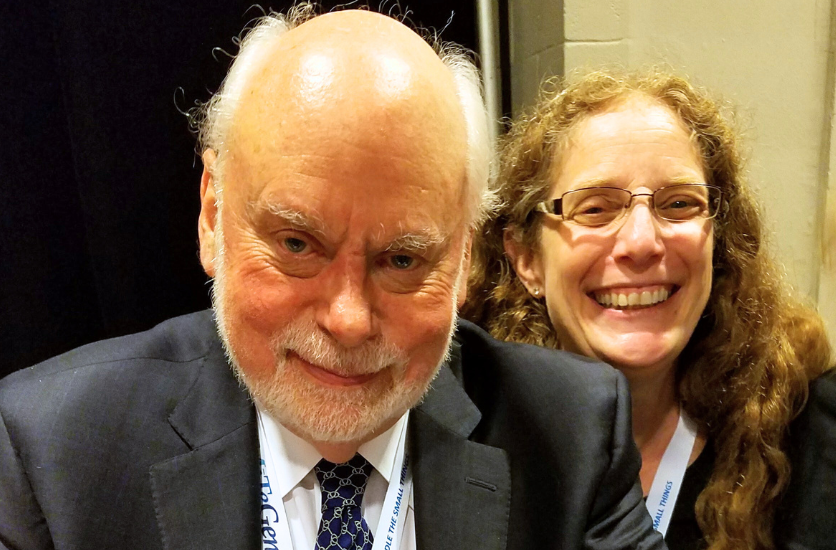

CHARLOTTE STERN

Charlotte Stern is an X-ray Crystallography Specialist at the Integrated Molecular Structure Education and Research Center (IMSERC). With 30 years of experience in crystallography, she was a frequent collaborator of Stoddart’s, contributing to many of his most highly cited papers. Learn more about her work in the Summer 2024 Newsletter.

As a Crystallography Core Scientist in IMSERC, what ways did you interact with Fraser Stoddart and what impact did he have on your career as a crystallographer?

I was fortunate to be able to work on structures for Fraser Stoddart’s group as they often presented me with some challenging crystallography. I grew as a crystallographer working on those structures. His research helped me to become more adept at looking into other characterization data to help support what we were seeing crystallographically when that didn’t necessarily meet with the students’ expectations. I also appreciated Fraser’s willingness to talk directly with us about some of the challenges we were facing. He respected us as scientists and subject matter experts in our field, which was refreshing.

crystallographically when that didn’t necessarily meet with the students’ expectations. I also appreciated Fraser’s willingness to talk directly with us about some of the challenges we were facing. He respected us as scientists and subject matter experts in our field, which was refreshing.

How did you see Stoddart’s influence shape the culture or direction of the Department during his time at Northwestern?

IMSERC wouldn’t be the same without Stoddart’s influence. He insisted that we would have a state-of-the-art facility that we could showcase to all. Which happened! His insistence that NU have a cutting-edge characterization and analytical facility was really what brought IMSERC to life as a center of collaboration and learning for students, staff and faculty.

What is a memorable story you would like share about working with Fraser?

One thing outside of IMSERC and Northwestern University, was Fraser’s willingness to engage with the next generation of Chemists. I remember back in 2017 when he gave the opening lecture at the ACA (American Crystallographic Association) in New Orleans – he stayed at the meeting for a few days so that he could meet with student attendees. At the YSIG (young scientist) Mixer, he had commandeered a table which was full of students, and he listened to their stories about life and research. His commitment to mentoring and inspiring the next generations of chemists will be sorely missed.

Margaret "Peggy" Schott

Margaret Schott, known to most in the Chemistry Department as Peggy, joined Northwestern Chemistry in 2008 to support Sir Fraser Stoddart upon his arrival. Holding a Ph.D. in Organic Chemistry from Northwestern, she applied her expertise by editing manuscripts and assisting in lab operations. Beyond her work with Stoddart, Peggy is an active member of the Chicago ACS and a passionate science historian. Learn more about her contributions in her Winter 2019 Staff Spotlight.

You studied in the department in the 1980’s returned in 2008 to support Stoddart’s arrival. From your perspective as an alum, how did Fraser Stoddart’s focus on innovation and interdisciplinary approaches shape the culture of the Department?

Fraser loved the chemistry department culture of “hunting in packs,” that is, collaborating on research with members of other groups. His full embrace of this interdisciplinary vision helped maintain that culture.

His strength in organic synthesis added to the department’s culture of excellence, and his publications gave a boost to the profile of the department on the world stage as reflected in the Thomson-Reuters/Clarivate citation rankings.

Fraser provided the initial impetus for the construction of a first-rate characterization facility (Integrated Molecular Structure and Education Center, or IMSERC), which represented a vast improvement over the previous Analytical Services Laboratory. Indirectly at least, this user-friendly facility spurred innovation in the department by offering high quality services and training on modern instruments.

Shortly after his arrival, Fraser started inviting faculty from his extensive global network to give lectures, both within and outside the department’s seminar series. These faculty visits infused a wealth insights and new chemistry, along with an opportunity for young people to meet with scientists from outside the university.

Sir Fraser gave new students and postdocs a long tether to work on projects they were excited about while still making use of “Stoddart chemistry”. Although he launched three companies, his idea of innovation was not tied up with practical applications; it was more about fostering discoveries, making something new that had not existed before. That said, he often instructed his group that, when planning a project, it should represent an incremental advance on previous work to have the best chance of success.

What impact did Stoddart have on you as both an employee and a chemist?

As a member of the Stoddart group, I attended weekly group meetings (journal club) and group therapy meetings (research presentations). As a result, my scientific knowledge was enlarged over time into completely new areas like supramolecular chemistry. I enjoyed the intellectual stimulation of editing scientific manuscripts. Although some of the topics were way over my head, my chemistry education and job experience were used in the best possible way.

From working with Fraser, I learned that is there is no type or amount of information—no matter how daunting—that cannot be organized into a sensible and accessible format, whether in writing or graphic illustration. For instance, a few years after his arrival at NU he formed a Faculty Honors Committee and proceeded to coordinate the nomination of chemistry faculty members for prizes and awards, with great success. Borrowing from his experience at UCLA, we created large spreadsheets to organize the nomination criteria from several societies.

On the personal side, working alongside Fraser was a confidence booster, as he frequently expressed admiration for my abilities and gratitude for the work I accomplished. When I would talk with him about certain decisions, such as running for an office in the local chemistry society, he invariably was supportive. He would say, “Why not give it a try? You’ll show them how it’s done!”

Serving on the staff as Fraser’s personal assistant was the opportunity of a lifetime. Prior to coming back to NU, I had been wondering where my career was heading. I came to realize that my niche was in higher education assisting other people, and I am proud of the important work and mentoring we accomplished on behalf of the research group. This opportunity was also ideal in that I could fully put into use the education I received from NU and especially from my PhD mentor Prof. Robert Letsinger.

What is one of your favorite stories from your time working with Fraser?

If something was going particularly well, Fraser might start singing an old familiar tune. Since the two of us were not very far apart in age (about a dozen years), we knew some of the same songs that were popular in middle years of the 20th century. For instance, he might sing a few verses of “If you’re happy and you know it, clap your hands…”, and I would join in. Another favorite was “Bicycle Built for Two” with its refrain of “Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer, do.” It was a lot of fun.

On one occasion, after Susan Boyle stunned the world with her singing voice on Britain’s Got Talent, Fraser delighted in watching the YouTube recording over and over again, showing it to anyone who came into the office. She was a fellow Scot, after all!

Remarkably, Fraser chose to use his Nobel Prize earnings – one third of a million Swedish krona – to pay for the hotel accommodations of the 60 or so friends and academic colleagues he had invited to join him in Stockholm. At the end of his Nobel Lecture, he showed a scrolling list of the hundreds of group members who, through years of effort in the laboratory, had made the prize possible.